Obituary: Alden Schwimmer (1925-2023)

April 12, 2024

“If I had to pick the three people who had the most to do with getting Star Trek into reality, they would be Gene Roddenberry, myself, and an agent at Ashley named Alden Schwimmer,” Oscar Katz, a Desilu vice president, once said. A prominent ten-percenter for above-the-line, behind-the-camera talent during television’s Golden Age, Schwimmer turns up in the origin stories not only of Star Trek but of The Twilight Zone, The Defenders, The Man From U.N.C.L.E., Get Smart, and Mission: Impossible. It’s a claim to fame that’s almost certainly unique, and Schwimmer, when he died on April 22 of last year at 97, had outlived nearly everyone else who had anything to do with putting those shows on the air.

The few surviving colleagues I could find remembered him with unqualified praise. “Alden was a very bright guy, very strong-minded. He certainly knew the agency business, knew how to judge character, knew how to make a deal,” said Jerry Leider, who joined the Ashley-Famous Agency in 1962. “He was an extraordinary agent. He was able to look after his own clients and also to run the agency.” Sandy Wernick, a veteran agent and manager who worked for Schwimmer at AFA in Los Angeles in the sixties, added in a statement: “What I remember most about Alden, who I consider to be one of my mentors, was his quiet strength and incredible sense of humor. He taught me all the basics of creating and packaging quality television.”

Born in Brooklyn on May 25, 1925, to a dentist and a homemaker, Schwimmer earned a purple heart in the Battle of Hurtgen Forest and worked as a disc jockey while attending New York University on the G.I. Bill. He entered the agency business as a client, sort of. An aspiring quipster, he persuaded the William Morris Agency to hire him as a messenger while, at the same time, repping him as a comedy writer. That hustle may have hinted at his true talents; although Schwimmer got at least one early job writing dubbing dialogue for foreign films acquired for US distribution, and saw a handful of his ideas and scripts bought and produced during and after his days as an agent, the money side of the business won out. He started at WMA as its “kinescope librarian” (where did that library end up?!) and in October 1952 became an agent in the syndication department. Schwimmer’s name surfaces in the trade papers during that period as a “script editor” for Foreign Intrigue, an independently produced, syndicated espionage drama with European location shooting as its selling point. It was an indication of how blurred the lines were between agency representation and production in early television, an overlap that emerges as the through-line in Schwimmer’s career.

In 1955 Schwimmer moved from the gargantuan WMA to the boutique Ashley-Steiner agency, to run a department repping television writers, directors, and producers. He replaced, and inherited some clients from, Jerome Hellman, at 26 an even younger wunderkind who was promoted to A-S’s packaging department. Hellman would soon leave to run his own agency for a few years before becoming a major producer (Midnight Cowboy; Coming Home; The Mosquito Coast) and a minor director. That path was one that Schwimmer would emulate – or try to.

Ashley-Steiner was a new company founded by a dynamic young insider, Ted Ashley, a nephew of a senior William Morris executive. Ashley, who had anglicized his name from Theodore Assofsky, was only three years older than Schwimmer. Ashley-Steiner’s first clients included some of the early stars of live television, among them Gertrude Berg and Mike Wallace. When Schwimmer started at A-S, mid-tier writers (Alvin Sapinsley; Loring Mandel) and directors (Robert Stevens; Paul Stanley) were the agency’s bread and butter. The most lucrative clients for Schwimmer’s department became those television writers who had enough name recognition to be a commodity. Ashley-Steiner’s strategy was to move those names away from one-off teleplays and into, first, exclusive network contracts (principally at CBS), then lucrative screenwriting gigs and ongoing series, which promised weekly licensing fees and maybe a pot of gold at the end of the syndication rainbow. The top writers at Ashley-Steiner were turned into brands – an early iteration of the modern idea of the television showrunner/auteur.

For Reginald Rose, Ashley-Steiner negotiated fifty percent ownership (shared with CBS) of his show The Defenders, a jaw-droppingly favorable split in an industry that was still scheming to keep “created by” credits off of ongoing series in order to deprive pilot writers of big royalties. It was Schwimmer who suggested “The Defender,” a two-part live Studio One about father-and-son lawyers, as a salable premise from Rose’s back catalog. Even the independent company that made The Defenders, Herbert Brodkin’s Plautus Productions, didn’t make out on the show as well Rose did – although Ashley-Steiner also repped Brodkin, and cleaned up for him, too, unloading Plautus’s rather uncommercial back catalog on Paramount for the equivalent of $20 million in stock shares. The Defenders, though it’s semi-forgotten today, was critical to Ashley-Steiner’s success in television – a multiple Emmy-winner as well as a minor hit, it established the agency’s credibility with the talent as well as the money men.

At some point Reginald Rose gently pointed out to Rod Serling that he had outgrown his agent, Blanche Gaines. Serling was picking up checks and reimbursing Gaines for long-distance calls: quit being a chump, Rose told him. Ashley-Steiner poached Serling and quickly put him together with William Dozier at CBS, which then bought an idea Serling had been floating for a while, without any takers. This was The Twilight Zone, and Serling, too, kept half the copyright to his creation. Later, Serling famously expiated his guilt over dumping Gaines in a Playhouse 90. It was Ashley and Steiner (or maybe Ashley and Schwimmer?) that Serling savagely fictionalized in “The Velvet Alley” as the corporate agents (played by Alexander Scourby and David White) who mock the Serling surrogate’s small-time ambitions. They tell him: “In this town, you’re either a giant or a midget.” A giant makes a quarter of a million dollars a year, and his agents want to make a giant of Ernie Pandish. The quotes that Schwimmer later gave to Serling biographer Joel Engel hardly sound any different from Serling’s dialogue in that scene: “He left Blanche because he needed a full-service shop – more than a mom and pop agency. That was the bullshit we gave him … I’m afraid that little lady in New York didn’t know how to do that, to package television shows and sell them and operate them after they’re on.”

*

I should interrupt myself for a moment to explain the “package deal,” a term originally coined by the flashy super-agent Charles Feldman (back to him in a second), and a tactic perfected by Lew Wasserman’s MCA. Unlike poor, discarded Blanche Gaines, a large talent agency representing clients in different but complementary fields has the leverage to bundle the services of those clients in take-it-or-leave-it packages. Often the agency doing the packaging would take a commission on the deal on top of its 10% of the artists’ fees; Ashley-Famous, for instance, received 5% of the licensing fee paid from networks to studios to produce TV shows in the sixties. This was, obviously, a conflict of interest, but since it was an avenue for bringing clients into the financial big-time, artists tolerated it. Historians tend to ascribe credit for the origins of a show or movie to the creative people whose names appear on screen, or more loosely to the studio or network that distributed the finished product. Agents – who by the sixties usually practiced a Wasserman-derived ethos of maintaining a low profile in the press – are often omitted or marginalized in the creation myths. But, in many cases, they were pulling the strings.

When the Department of Justice forced the goliath MCA out of the agency business in the early sixties – MCA had been flagrantly self-dealing for a decade with its television production company Revue, and finally triggered an anti-trust investigation after it bought a movie studio (Universal) and a record label (Decca) – a seismic wave rolled through the talent side of the business. Ashley-Steiner was the major beneficiary. Ashley, who had already started buying up smaller agencies, picked up some twenty former MCA agents and about 300 of their clients, and soon merged with Feldman’s company Famous Artists. As its name promised, Famous added the last ingredient needed to elevate Ashley’s enterprise into the top rank – movie stars, including John Wayne, Ingrid Bergman, and William Holden, as well as film directors like Howard Hawks and George Stevens. Feldman soon sought a buyout to produce movies, leaving Ashley, barely 40, atop the third-largest talent empire in the industry.

Alden Schwimmer went west, young man, just prior to the merger, in 1961. Ashley dispatched him to Los Angeles to work under Steiner, who ended up being the major casualty of the reshuffling. In 1964 Steiner left with the agency with the usual consolation prize, a producing shingle, and Schwimmer was promoted to run the Hollywood office: Ashley’s top man on the Coast. While Ashley was often depicted in the press as the next big media mogul (a prophecy that came true), Schwimmer rolled his eyes at the trappings of show biz and kept a much lower profile (which makes it difficult, now, to document which pies he did or did not have a finger in). He complemented his boss. As Schwimmer’s son John put it, referencing a distinction made in L.A. Law-type legal firms, Ashley was the “finder” and Schwimmer was the “minder and grinder.”

(A parenthetical parting wave to Ira Steiner, who started as a band booker in the thirties, like Lew Wasserman, and may have been to Ted Ashley what Jules Stein was to Wasserman, or Al Levy to David Susskind – the long-suffering mentor figure, cast aside or kicked upstairs by the protege. He ended up with only a single producing credit, on the Burt Lancaster western Valdez Is Coming, and died in 1985.)

By 1962, the bulked-up A-S-F roster read like a who’s who of television: Bob Banner (Omnibus; The Dinah Shore Chevy Show), David Dortort (Bonanza), Herbert B. Leonard (Route 66 and Naked City), William Self (Peyton Place and Batman). Ashley’s agents took over packaging The Ed Sullivan Show, talked Danny Kaye into doing television on a hit CBS variety hour, and rebooted that network’s faltering The Garry Moore Show by attaching Banner as its new showrunner. It was rumored that Ashley had helped to engineer James T. Aubrey’s ascent to the presidency of CBS, and that the network in turn favored his clients.

In Los Angeles, Schwimmer’s key client during this period was Norman Felton. British-born Felton, the longtime producer-director of the live Robert Montgomery Presents, had moved to Los Angeles, set up shop under the banner Arena Productions, and landed the job of reviving a dusty old MGM doctor movie franchise for television. Thanks largely to its hunky star, Richard Chamberlain, Dr. Kildare was a hit.

*

On paper an indie outfit headed by a prominent creative, Felton’s Arena Productions can be better understood as a sort of front for Ashley-Famous. This was a common arrangment after MCA got trust-busted; Danny Thomas Productions and Dick Powell’s Four Star Productions, for instance, were not truly independent companies so much as they were packaging structures operated by the William Morris Agency. Bing Crosby Productions was operated in practice by the crooner’s agency, a relatively small one run by George Rosenberg, whose wife Meta – the prime mover in the company – even wrangled the creator credit on one BCP show, Breaking Point. It was that world in which AFA sought to gain ground.

At the beginning of the 1963-64 season, Ashley-Famous claimed credit for packaging ten prime-time series, out of fewer than 100. And the agency wasn’t just peddling flesh; as Albert R. Kroeger explained in a 1963 Television article:

Selling shows is only one function of a big agency like A-S-F. It often creates the basic concept of a series, adds the elements of a writer, producer, director, performers, acts in business areas of ad agencies, sponsors, networks. When a show is on, it services it, books talent, takes care of the many problems that can crop up.

For a dozen or more hit shows in the sixties, it was Schwimmer who did the servicing. The earliest ones came out of Arena. For NBC’s peacetime military drama The Lieutenant, Schwimmer put his client Gene Roddenberry, a writer of some good Highway Patrol and Have Gun – Will Travel episodes, together with Felton. Ashley-Famous also represented The Lieutenant’s star, Gary Lockwood, and the pilot director, Buzz Kulik: a typical package deal. Schwimmer also first hatched the idea, the week after Dr. No opened in theaters, of acquiring an Ian Fleming property for Felton to produce for American television. The Man From U.N.C.L.E.’s creation story is convoluted – the initial Schwimmer pitch, a Fleming travelogue still in galleys called Thrilling Cities, appealed to no one, and Ashley and Jerry Leider from the New York office ended up as the Fleming whisperers for a thin premise (Solo) that Felton hired writer Sam Rolfe to developed into the U.N.C.L.E. series.

Arena was Schwimmer’s first foray into television-indie sockpuppetry, and Ashley-Famous took credit for packaging its subsequent shows, the spinoffs The Eleventh Hour and The Girl From U.N.C.L.E. and the World War II actioner Jericho. None of those were hits and Felton’s empire crumbled; his credits were undistinguished after the mid-sixties. Soon a bigger indie would prove more useful for the agency: Lucille Ball’s Desilu Productions.

Run with some skill in its early days by Desi Arnaz, Desilu foundered after Ball divorced and ousted her abusive, alcoholic spouse and partner. Ball and her next spouse and partner, comedian Gary Morton, had no aptitude for developing projects, and stocked the company’s board and executive ranks with useless flunkies (including Ball’s brother Fred); by default, the primary decision-maker was Ball’s lawyer, Mickey Rudin. Desilu got by on studio space rentals to outside companies and a $600,000 slush fund from CBS, used to develop increasingly unsellable new shows. Apart from Ball’s eponymous sitcom, Desilu hadn’t launched a hit since The Untouchables in 1959, and didn’t sell a single pilot for the 1964-65 season. To a certain extent CBS was willing to throw money away to stay in the Lucy business, but some changes were in order.

On April 1, 1964, Variety reported that Oscar Katz, a loyal but expendable executive who had spent 26 years at CBS and been passed over for the top programming job by both Hubbell Robinson and Michael Dann, was leaving the network for a new job as Desilu’s executive vice president in charge of production. He also got a seat on Lucy’s board. Two weeks later, it was reported that Desilu had switched agencies, dropping General Artists Corporation (GAC) to become a client of Ashley-Famous.

At least that’s how the trade press characterized those moves for public consumption. Here’s how Alden Schwimmer explained it two decades later, in Patrick J. White’s The Mission: Impossible Dossier:

We needed a figurehead …. We never expected Oscar Katz to be a creative genius and he wasn’t. He was a decent, honorable, intelligent man who knew what he could and could not do. We brought Oscar in because we wanted a free hand there. I didn’t want anybody as the head of Desilu who was going to give me trouble and tell me he didn’t like the project.

Schwimmer set up his own office at Desilu (perhaps only briefly; this may have been going a bit too far) and began spending that sweet, sweet CBS money on long-term contracts for AFA clients. Pink Panther producer Martin Jurow, comedy writers Cynthia Lindsay and Hal Goodman & Larry Klein, and all-purpose writer/producers Robert Blees, Allen H. Miner, and Norman Lessing, among others, signed to develop three pilots apiece, for a fee of $50,000 to $60,000. The purpose of the spring hiring spree seemed to be the August 18 Desilu shareholders meeting, at which Katz bragged that the company had 22 pilots in the works, five of which were being produced “in association” with one of the three networks. That implied an upfront investment and a likelier commitment to buy, but of the projects Katz mentioned by name only one – something Variety typo’d as “Tar Trek,” partly financed by NBC – would get on the air.

Herbert F. Solow, a Desilu executive who moved in on Katz’s territory and would replace him in 1966, liked “Schwim,” called him a “warm, intelligent, fair-minded New Yorker with a very urbane sense of humor,” but in his book Inside Star Trek Solow was very clear about what was going on here: Schwimmer was steering more lucrative jobs to the star clients (Solow called them “superwriters,” mentioning Rose, Serling, Howard Rodman, and sketch comedy guru Tony Webster as examples) and sticking Desilu with journeymen writers who could use a career boost.

Schwimmer, interviewed by White in the eighties, was also pretty frank about where the actual power resided:

There was a giant conflict of interest which had to be handled very delicately. If you represent one side of the deal (the writer), you want to get the best deal for him; if you also represent the buyer, you want to buy for as cheap as you can. You had to be a diplomat and know how to make everyone content that it was a fair deal for all parties …. It is very rare that an agent has the power to give his clients wonderful deals. That’s what I had, this Desilu money to spend on my clients. Obviously, the ultimate responsibility was to make something good come out of it, which I did, but it was a hell of a thing which I had going.

The good that came out of it began with Star Trek, an idea that had its origins during the period when Roddenberry and Felton were working on The Lieutenant at MGM. Roddenberry pitched a premise about a dirigible exploring the United States in the late 1800s, and Schwimmer has been credited with revamping the concept as science fiction, on the theory that the topicality of the Space Race would make it more commercial. Star Trek sold to NBC and limped along for three seasons – albeit with an afterlife that Schwimmer no doubt took pride in. But at the time, Ashley-Famous’s more obvious success was with another mid-level writer whose deal with Desilu, curiously, was never touted in the trades like the others: Bruce Geller.

Geller – a would-be musical-comedy lyricist; no wonder he and Schwimmer clicked – had been an Ashley-Famous client since 1958, a young writer who won some awards for experimental (by network TV standards) dramas he wrote or produced at Four Star in the early sixties. But he hit an infamous speedbump when CBS fired Geller two thirds of the way through a truly weird season of Rawhide; Schwimmer probably parked him at Desilu right after that career nadir, in early 1965. By the end of the year the cameras were turning on Geller’s first project there. At the height of Bondmania “spy stuff sells” may not have been an insight of towering genius, but someone had to make it, and so Schwimmer prodded a reluctant Geller (who knew those convoluted caper plots would be a chore to write) to dust off a last-days-of-Four Star outline called Briggs’ Squad that he’d conceived in imitation of the heist movie Topkapi. The retitled Mission: Impossible ran for seven seasons, and then Geller topped it with the following season’s private eye drama Mannix, which lasted for eight. Though it had a premise devised by credited creators William Link and Richard Levinson, Mannix likely rose from the ashes of The Outsider, a Geller/Mike Connors/Talent Associates package that AFA had nearly sold to CBS just before the Rawhide kerfuffle.

Though no one involved with the original Star Trek or Mission: Impossible could have imagined it at the time, the two franchises that are keeping Paramount in business during the present century have their origins at Desilu in 1966. And it’s not much of a stretch to say that Schwimmer sold both of those shows to himself. All roads lead to Alden: It was Schwimmer who found discarded bottom drawer ideas in Roddenberry’s and Geller’s files, and Schwimmer who hand-picked the executive who greenlit them at Desilu. Throughout the run of Star Trek, Schwimmer enjoyed “instant access” to Roddenberry. Schwimmer tweaked the initial premise of Star Trek, suggested its proposed spinoff “Assignment: Earth,” and when Roddenberry decided to cut his losses ahead of the show’s lame-duck third season, it was Schwimmer who engineered his exit, bringing in another client, Fred Freiberger, to take over hands-on production. Why, then, is Schwimmer a peripheral figure rather than a central one in every history of Star Trek?

*

It’s hard to get one’s arms around just how many TV, and to a lesser extent film, projects Schwimmer touched during the sixties. AFA’s Beverly Hills office packaged the Lee Mendelson/Bill Melendez Peanuts specials and NBC’s Ron Ely-starring Tarzan series; indeed, Schwimmer, repping the Edgar Rice Burroughs estate, secured Roddenberry’s first post-Star Trek paycheck for a Tarzan feature script that wasn’t produced. “Superwriter” Tony Webster was the original head writer for The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour, and Ashley-Famous had a role in putting together The Carol Burnett Show and The Doris Day Show, too.

Finally there was Talent Associates. (Itself an agency that had shifted focus to TV production! It’s turtles all the way down.) This was initially a New York account; TA’s principal, David Susskind, had been with Ashley since the mid-fifties. But the demise of the anthology drama, and Jim Aubrey’s execution of East Side/West Side, Susskind’s expensive bid for Defenders-style prestige, left the company on the brink of bankruptcy. Then – provocatively, also in April 1964, the same month Schwimmer installed Oscar Katz at Desilu – the comedy writer-producer Leonard Stern joined Talent Associates as a full partner and set up a beachhead on the West Coast. Stern launched two big hits right out of the gate – Supermarket Sweep (which mortified Susskind) and Get Smart – and turned Talent Associates around overnight. The subsequent sitcoms Stern created – Run Buddy Run, The Hero, The Good Guys, and the critically acclaimed He & She – were not hits, but at least the networks were buying them, and TA was viable enough by 1968 for the partners to sell the company (to Norton Simon), which was probably the goal all along. The pattern looks strikingly the same as with Desilu – infusion of new blood, revival, sale (for Desilu, too, was sold, to Paramount, around the same time, as soon as the Roddenberry and Geller shows got going). The trade papers did describe Run Buddy Run and The Hero as Ashley-Famous packages, and Alden Schwimmer and Leonard Stern were neighbors; their sons hung out together, often at tapings of Stern’s shows. But I can’t find a smoking gun to confirm my hunch that it was chiefly Schwimmer who rescued Talent Associates.

*

Though he could have inherited many of Feldman’s celebrity clients if he’d wanted to, Schwimmer seems to have preferred his original wheelhouse, television, and left the starfucking to the former Famous agents. It’s easy to understand the appeal of television – it was comparatively less glamorous, but a bigger department and greater profit source for AFA than features. And Schwimmer, the hopeful gag writer, may have preferred the company of the agency’s more cerebral clients. He consistently turns up in books about his writers and their shows as a hands-on ally. Schwimmer was the sounding board for their gripes and their Mr. Fix-It for major and minor messes; Rod Serling, for instance, had trouble telling anyone no, so Schwimmer dutifully followed behind, undoing the verbal writing and speaking commitments that Rod let himself get dragged into at parties. He played practical jokes on Serling, bought Gene Roddenberry’s rock-tumbling equipment when Roddenberry tired of the hobby (or needed some quick cash), and owned a twin-engine airplane with Bruce Geller and another Ashley-Famous agent, Joel Cohen. By the time Geller crashed the Cessna and died in it, Schwimmer had sold his interest in the plane, but it still fell to him to call Jinny Geller and tell her she was a widow.

*

The trajectory of Lew Wasserman was so propulsively toward studio moguldom that it was probably inevitable his closest imitator and successor would take the same path. In 1967 Ted Ashley sold his agency to Kinney National Service, a voracious media conglomerate recently born out of a mobbed-up parking lot franchise. Then he persuaded Kinney’s CEO, Steve Ross, to buy him a movie studio to run: Warner Bros. Like MCA, Ashley had to get out of the talent business, and he unloaded the agency on a big-time small-timer named Marvin Josephson (who would eventually merge the remnants of AFA into the mega-agency ICM). Ashley took Jerry Leider with him to Warners, and many assumed that Schwimmer would go too – Variety even announced it. But instead Schwimmer cashed out. The reasons why remained opaque to Leider, and even to Schwimmer’s son, although Leider agreed with my guess that Schwimmer must have had some sort of falling out with either Ashley or Ross during the transition. In any case, he entered the seventies with a lot of dough but little power and not enough to do.

Like most high-level agents or executives who lose out at corporate musical chairs, Schwimmer launched his own company, Cinema Video Communications, Inc., together with a pair of reliable creative hyphenates, Bruce Geller and Pink Panther auteur Blake Edwards, and a wild card: Harold Robbins, the vulgarian celebrity author of highly filmable hack novels. Robbins should have been a cash register, but his partners had trouble getting any work out of him. “Robbins was basically lazy and was interested in having fun,” Schwimmer told the novelist’s biographer. CVC announced a diverse slate of upcoming projects in the trades: three pilots for ABC, including the “family western” Kentucky Belle and a science fiction item called The Guardians; features adapted from David Chandler’s novel Huelga! (about Chicano migrant workers), Kingsley Amis’s The Green Man, and Cornelius Ryan’s The Peacemaker. That last one didn’t exist, and never would: Ryan, the author of The Longest Day, was a close pal of Robbins’s who was dying of prostate cancer.

The make-or-break property for the company was another unwritten book, Robbins’s forthcoming The Betsy, which CVC sold to Warner Bros. on favorable terms. But when the novel came out the reviews were scathing, even by Robbins’s standards, and Warners quickly canceled the deal, officially because CVC’s $4 million budget was too high. (Unofficially: Was it really because the book was crummy, which tended not to trouble Robbins’s target audience, or did Ted Ashley have some reason for sticking it to his old right-hand man?) Robbins blamed his partners and left the company. Edwards had already pulled out the year before. That left Schwimmer and Geller, who set up an original script by a pair of Mission: Impossible writers at United Artists, with James Coburn attached to play a professional pickpocket. Harry in Your Pocket was to be Schwimmer’s only producing credit, Geller’s only feature as director, and CVC’s last gasp. As a producer Schwimmer was to be an Ira Steiner, not a Jerome Hellman.

After that Schwimmer took a sharp turn so unusual that the Los Angeles Times ran a puff piece about it: “He Gives Up Show Biz For Life in a Courtroom.” Schwimmer went to law school in 1973, and spent much of the late seventies and early eighties as a practicing attorney – not negotiating entertainment contracts, as one might have expected, but prosecuting criminal cases for the Los Angeles County District Attorney’s Office. After that, he pursued his hobbies – boats, planes, sports, gadgets – with the drive of the dealmaker he’d once been, and still flirted with another Hollywood comeback. Along with penning a few scripts, Schwimmer took a job for an old client, Danny Arnold, as a producer on the Peter Boyle comedy Joe Bash (his daughter worked on the show, too). Had the series lasted for more than six episodes, Schwimmer might have spent his later years on studio lots.

One other project from his (semi-)retirement merits a mention: In 1980 Schwimmer and his wife Nina, an interior decorator, bought a plot of undeveloped land far up in the hills of Benedict Canyon and commissioned John Lautner to design a residence there. It’s a snazzy house, but it’s also kind of a shame that it’s almost all that comes up on the internet when you search Alden Schwimmer’s name.

Above: Alden Schwimmer is standing on the right; Ted Ashley is seated in the center; Hume Cronyn (of course) is holding the pipe; and is that Jerome Hellman at the top left? If so, the photo is likely from 1955-57. Alden Schwimmer portrait at the top is by (I think; it’s hard to read) Marquet, Forest Hills, N.Y. Photos courtesy John Schwimmer, who also supplied most of the biographical details about his father’s life before and after Alden Schwimmer’s agency career.

Playhouse 90 Redux

March 17, 2024

It’s time to fix something that’s been bothering me for (exactly!) ten years.

Presented below is the “writer’s cut” of a piece from 2014 that was mangled badly during the editing process. If you had the misfortune to come across it in its bastardized form, then I hope enough time has passed so that the essay which appears below will seem fresh.

Between 2013-2016 I wrote sixteen feature articles for The A.V. Club, plus a handful of capsules for “listicles” by multiple contributors. Before I throw anyone any further under the bus, I should clarify that my experience with the editing process was either positive or neutral on all but one of those full-length stories; and that overall I held the editorial staff in high regard (especially Emily St. James, who recruited me to write for AVC, and was not responsible for the revisions I objected to in this instance). I left something cringeworthy in one of the “Random Roles” interviews and a junior editor did me a favor by taking it out. My infamous Breaking Bad takedown was a contentious edit, with extensive notes from multiple staffers and a publication delay, but a ultimately a productive one. Emily shielded me from the office politics (I found out later that one of the editors-in-chief was a Breaking Bad superfan who wanted to kill the piece entirely) and wrote something that made me realize the flaw that was setting people off was in the tone, not the content. So I did a pass to soften any phrasing that was harsh or sarcastic, making the contrarian argument as neutrally as I could manage in the hope that readers would be more open to it that way. Thanks to that note, the final draft was much better than the one I handed in, which is how it’s supposed to work.

But everything bad that can happen on a freelance assignment happened to poor Playhouse 90. There were cuts for length that were probably justified, but still damaged the piece structurally; a short section was rewritten to alter its meaning, over my vehement objection; my own revision in response to those changes was submitted ahead of an agreed-upon deadline, but nonetheless ignored without explanation; and the “fact-checking” process introduced at least one embarrassing Wikipedia-sourced howler. Although it was routine to request corrections post-publication, that error remains in the piece as published at AVC (See if you can spot it! Actually, don’t.), just because I was so livid that I didn’t trust myself to contact anyone on the staff for a month or so.

Because of the unsanctioned changes to the text, I effectively disowned the piece, opting not to promote it on social media or participate in the comments section (which was encouraged by AVC staff, and which I enjoyed). I did acknowledge its existence obliquely, and buried a link to it, on this blog, only because I had prepared two sidebars (a listicle of parentheticals and footnotes that couldn’t fit into the main piece, and a brief interview with Playhouse 90 story consultant Joy Munnecke) that I was too vain to spike.

To give credit where it’s due, some of the editorial input was beneficial. This version is therefore not my original draft; it’s a hybrid that reverses the unwelcome deletions and rewrites, but also incorporates some of my second-draft revisions. I had no complaint with the headline The A.V. Club ran it under (I think the change was just to reduce the character count, which had a design-imposed limit), but the title below is what I submitted.

The 2014 version is still out there, albeit minus the embedded video clips and rendered partially into gibberish due to the sad, Spanfeller-era neglect of AVC’s archives, but my strong preference is that citations refer to this post instead.

*

The super-sized dramatic anthology Playhouse 90 was an elegy for live television

by Stephen Bowie

More than any other single series, Playhouse 90 has come to represent the legacy of live anthology drama. Although most of its 134 episodes are frustratingly out of circulation, three of them have been revived over the years on PBS and home video, most recently as part of a Criterion DVD box. Rod Serling’s “Requiem For a Heavyweight,” which swept the 1957 Emmy Awards and put Playhouse 90 on the map in terms of critical acclaim, examines the aftermath of a punchy boxer’s last fight. Although it’s set in scuzzy gyms and bars, Serling finds a soft center: the heart of the story is the tentative romance between Mountain McClintock (Jack Palance) and the employment counselor (Kim Hunter) who tries to help him find dignity and purpose. Their scenes together, in which Palance reveals that the brutish-looking Mountain has a shy, sensitive soul, channel the emotional delicacy of Paddy Chayefsky’s Philco Television Playhouse segment “Marty,” which prior to the arrival of Playhouse 90 was widely acknowledged as the high-water mark of live television.

“The Comedian,” Serling’s adaptation of an Ernest Lehman story, stars Mickey Rooney in a terrifying, unhinged performance as the kind of nakedly narcissistic star (think Milton Berle or Jackie Gleason) that the new medium had minted in its formative years. JP Miller’s “Days of Wine and Roses” was The Lost Weekend as a duet, a harrowing take on alcoholism in which heavy-drinking lovers (Cliff Robertson and Piper Laurie) are torn apart as one gets sober and the other cannot. “Days of Wine and Roses” was eventually remade as a very good movie, as were “Requiem” and several other segments, including “The Miracle Worker” and “Judgment at Nuremberg.” The film versions have displaced the abandoned-in-the-vaults originals in our cultural memory, but Playhouse 90 came first.

“We had some stinkers,” said the author Dominick Dunne, who worked as a production coordinator on the series. “But when it was good, it was great.”

Act One: Program X

Playhouse 90 began as a pitch by Dr. Frank Stanton, CBS chairman William S. Paley’s formidable, forward-thinking right-hand man, during a brainstorming session for program ideas. But the project was developed by Hubbell Robinson, a CBS vice president who received no screen credit on Playhouse 90 but is often described as its creator. Along with NBC’s Sylvester “Pat” Weaver, Robinson was one of the most vocal early advocates for quality television. The idea that the medium should aspire to some cultural significance, apart from its primary function as a source of revenue, became increasingly embattled in the late fifties, as popular cookie-cutter Westerns and situation comedies appeared to affirm an audience craving for unchallenging fare. With a wearying regularity, Playhouse 90 became the front line on that battlefield of culture versus commerce.

Developed under the placeholder title Program X, Playhouse 90 was an outgrowth of the ninety-minute and two-hour “spectaculars” that had been a fixation of Weaver’s at NBC. Stuffed with all-star casts and often broadcast in color, the spectaculars were part of an ongoing arms race with the movies. Hollywood, its profits threatened by television, had rolled out CinemaScope and stereo sound, and now television was countering with bigger and better reasons to stay home. Both networks had created weekly series comprised of spectaculars (NBC’s Producers’ Showcase and CBS’s Ford Star Jubilee), but the material was usually light in nature: comedies, musicals, festivals of opera or jazz. It was Robinson’s inspiration to combine the scale of these programs with the gritty, “kitchen drama” aesthetic of the dramatic anthologies.

Robinson put out the welcome mat for underpaid artists. Teleplays would fetch $7500, and top directors who had been earning $400 a week could command $10,000 for a single Playhouse 90 segment. The show’s widely publicized, $100,000-per-episode budget was high enough that CBS had to enroll three or more sponsors, which necessitated a whopping nine commercial breaks. Episodes of Playhouse 90 feel choppy even by the standards of modern network television’s forty-minute hour. Robinson and his newly-hired producer, Martin Manulis, had to break it to the writers that their three-act plays were about to become six-act plays, with a surfeit of artificial climaxes.

A sophisticated veteran of the New York theater, Manulis had a rare ability to earn the confidence of both the creative types and the network suits. Two years earlier, Manulis and his star director, John Frankenheimer, had rescued the live anthology Climax from a creative downward spiral that, er, climaxed with a broadcast in which an actor playing a corpse stood up and walked off the soundstage in full view of the camera. (CBS fired the original producer the next day.) It was Manulis who made Playhouse 90 a hit.

Act Two: Television City

Climax was the first major prime-time anthology broadcast live from Los Angeles, rather than New York City, from the beginning to the end of its network run. Playhouse 90 became the second and last. Although many of the “Golden Age” writers and directors looked down on the West Coast as the place where artists went to sell out, Los Angeles was a fait accompli. One of the reasons CBS had mounted the project in the first place was to get some use out of Television City, a new complex at Beverly and Fairfax that still stood mostly empty in 1956. For technophiles like Frankenheimer, the new studio was a kid’s toy box: a huge, state-of-the-art facility that could accommodate bigger sets and more cameras (four became the norm for Playhouse 90, but some episodes deployed as many as seven) than any television studio in New York.

Manulis set out to court the best of the newly famous television writers – and indeed all of them, save for Chayefsky and Gore Vidal, would eventually contribute to Playhouse 90 – and paid homage to them with an unprecedented “audio credit.” (“Written especially for Playhouse 90!” the show’s announcer bellowed, even when a script hadn’t been.) But the scale of the endeavor meant that the true auteurs of Playhouse 90 were the directors.

Manulis gave Frankenheimer every third episode, and first choice of scripts. Alternating with him were another CBS contractee, Vincent J. Donehue, and freelancers Arthur Penn and Ralph Nelson, each hired for six segments. Later Franklin Schaffner became the most prolific director after Frankenheimer, and George Roy Hill, Fielder Cook, Delbert Mann, Robert Mulligan, and Sidney Lumet joined the rotation. Most of these men leapt immediately from Playhouse 90 into feature film careers, and they would direct some of the best American movies of the following decade: The Manchurian Candidate, To Kill a Mockingbird, The Pawnbroker, Bonnie and Clyde, Planet of the Apes, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. If the “kitchen” school of television writing peaked somewhere around “Marty” (1953) or Serling’s “Patterns” (1955), live television as a visual medium did not reach its full potential until it moved into Television City.

Each director had his own hand-picked technical crew and, atypically for television, Manulis allowed the directors to select much of their own material. Frankenheimer went on a literary kick and turned his favorite modern classics by Fitzgerald, Hemingway, Odets, and Faulkner into Playhouse 90s. “The Miracle Worker,” about Helen Keller and her teacher, was a passion project that Arthur Penn had tried to get made on earlier anthologies. In “Invitation to a Gunfighter,” a “Western without horses” (because, as story editor Del Reisman pointed out, horses had a habit of relieving themselves on camera), and “Portrait of a Murderer,” about the real-life killer Donald Bashor, Penn tries out innovative themes and approaches that would recur in his first film, The Left-Handed Gun, and Bonnie and Clyde. “Portrait of a Murderer” makes extensive use of Bashor’s actual statements and a first-person camera to create a faux-documentary style that was decades ahead of its time. Penn marveled at the “improvisatory aspect” of Tab Hunter’s performance as Bashor, citing an unplanned moment in which Hunter stops to pick up a basket of spilled laundry just after his character has committed murder. It was a textbook case of how the immediacy of live television was meant to work.

But Frankenheimer set the style of Playhouse 90 more than anyone else. Only twenty-six when the series debuted, Frankenheimer was a decade younger than most of the other directors. He projected a total confidence that tended to win back many collaborators initially alienated by his brusque demeanor. “There was very little discussion, or leeway, with him,” said Reisman. “That can be very effective, particularly for actors who are thinking, ‘Well, I’m not quite sure of this.’ Veteran actors accepted his direction.”

Frankenheimer projected himself into the work, literally. He composed shots by moving through rehearsals in place of the camera, so that actors were often startled to turn and find his face inches from their own. While Frankenheimer was justly lauded for his rich imagery – which favored wide-angle lenses and a blend of both long takes and complex cutting – in Playhouse 90 he also displayed a command of performance that was at best intermittent in his subsequent film career. The love scenes in “Winter Dreams,” a rich girl-poor boy romance adapted from an F. Scott Fitzgerald story, have a fervid delicacy; the last ten minutes consist of just the stars, John Cassavetes and Dana Wynter, murmuring to each other in front of a fireplace. Sterling Hayden, playing desensitized brutes awakened by love in two of Frankenheimer’s best episodes (“Old Man” and the visually dazzling science fiction piece “A Sound Of Different Drummers”), and Robert Cummings, totally unsympathetic as a cruel Air Force officer in “Bomber’s Moon,” created fearless critiques of masculine stoicism. And in the squalid motel-room set of “Days Of Wine And Roses,” Piper Laurie performed the screen’s definitive drunk scene, finessing precise notes of anger, seductiveness, self-pity, self-hatred, and a dozen other emotions.

The married Frankenheimer had brief but passionate affairs with Laurie during “Days” and with Janice Rule (memorably ferocious as a brilliant manic-depressive) while making the group therapy drama “Journey To The Day,” and at least an infatuation with Wynter (“perhaps the most beautiful woman I’ve ever seen”), the star of “Winter Dreams” and another Frankenheimer segment, “The Violent Heart.” During rehearsals the author of “Days,” JP Miller, complained that Frankenheimer was neglecting Laurie’s co-star, Cliff Robertson, in order to fine-tune her drunk scenes, prompting producer Fred Coe to offer the director a witty critique: “You’ve got the wine, now see if you can get the roses.” But Laurie’s excellence in the broadcast affirmed the aptness of her director’s focus. Romances between great directors and their leading ladies (or men) are a cliche of the cinema, but the corporatized two- and five-day schedules of early television production rarely permitted them. That Frankenheimer and his actresses ended up channeling off-screen intimacy so productively into their work was a consequence of the artist-indulgent environment of Playhouse 90, which permitted directors and actors to spend weeks or even months preparing each segment. In many ways beyond its extended length, Playhouse 90 emulated the methods and the creative aspirations of feature filmmaking, bridging a gap between mediums that were much farther apart in the fifties than they are today.

As gripping as his best projects were, Frankenheimer also ended up directing treacly family fare like “The Family Nobody Wanted” and “Eloise” (based on the children’s book). If the main emphasis was on the “Marty” school of quality television, CBS still hedged its bets by insisting on occasional comedies and specials, like a color broadcast of George Balanchine’s ballet The Nutcracker for Christmas 1958 and, indefensibly, a “party” to celebrate the one-year anniversary of the film Around the World in 80 Days. (Who took home that payola?) Even though he felt the “excitement” was in original scripts, Manulis had no compunction about dusting off an old chestnut or two. “I tried to balance all the hifalutin stuff with Johnny Carson and Carol Channing doing Three Men on a Horse,” he said.

Ostensibly to give the live crews a rest, but probably to break up the challenging dramas with something more traditional (and cheap), CBS hired Screen Gems (and later Filmaster and Universal) to film some westerns and melodramas that would run about every fourth week. “They were dreadful,” said production supervisor Ralph Senensky. Most of the live Playhouse 90 staff tried to pretend the filmed shows didn’t exist, and CBS discontinued them after the second season.

Act Three: Summer Stock in an Iron Lung

For CBS, another part of the allure of Los Angeles was access to movie stars. Stunt casting was a network mandate from the start, even inspiring the visual motif of the opening titles and interstitials: sponsors’ products, the rotating hosts (usually one or more stars of the following week’s episode, then in rehearsals), and sometimes even the principal actors themselves were introduced against a black backdrop surrounded by chintzy papier-mache stars dangling from above.

Playhouse 90’s casting director, Ethel Winant, was one of the most influential women behind the camera in early television; although she never received credit as such, Winant was in effect Playhouse 90’s “invisible producer” (in John Houseman’s words), advising on matters outside of casting and functioning as a liaison to the network. Winant mitigated the celebrity decree somewhat by casting against type as often as possible. “Ethel was really good about finding the other side of somebody,” said Manulis.

Stunt casting yielded some unexpected gems, like matinee idol Hunter (fortunately filling in for first choice Robert Wagner, whom Twentieth Century-Fox declined to loan out) in “Portrait of a Murderer,” oily sitcom star Cummings in “Bomber’s Moon,” singer Mel Torme as “The Comedian”’s spineless brother, and horror icon Boris Karloff as Kurtz in “The Heart of Darkness.” But just as many Playhouse 90s were sunk by a star shoehorned into the wrong part: comedic actor Tony Randall as a Gatsby-ish social climber in “The Second Happiest Day,” the veddy British Charles Laughton as a Polish rabbi in “In the Presence of Mine Enemies,” and Jack Palance as a frail Jewish movie mogul in “The Last Tycoon” and a Spanish bullfighter in “The Death of Manolete.” Somehow Winant came up with smarmy musical comedy star Jack Carson for the role of a career military officer in “The Long March,” adapted from the William Styron novel. In an early scene Carson stumbled over the tongue-twister line “tank tactics,” and for the rest of the show he stammered constantly, looking like a deer caught in headlights and throwing off the other actors’ concentration.

“The Long March” was one of Playhouse 90’s legendary on-air disasters, of which there were more than a few. “The Death of Manolete” was the most famous, thanks to Frankenheimer’s dubious judgment that a bullfight could be simulated with a pair of antlers mounted on a cart. The funniest occurred during “In Lonely Expectation,” a ensemble piece about the limited options faced by young women in a home for unwed mothers. At the climax, when one of the women decides to keep her baby and leave the home, the actress (Susan Harrison) tripped and dropped the “baby” (a doll, fortunately), which tumbled halfway down a tall staircase: thud, thud, thud. After an endless moment of stunned silence, someone picked up the doll and handed it to Harrison, and the actors tried to carry on as if nothing had happened. “Well, there goes the rerun,” quipped the technical director.

The pressure involved in mounting a show under those conditions was, of course, enormous. The analogy everyone loved to use – Frankenheimer attributed it to the character actor Sidney Blackmer – was “summer stock in an iron lung.” Only adrenaline junkies thrived making Playhouse 90. It’s no coincidence that the generation that came of age in live television was also the generation that had fought World War II – Serling had been a paratrooper, Penn a veteran of the Battle of the Bulge, Hill a bomber pilot who liked to compare the television control room to a cockpit. The war was Playhouse 90’s favorite subject: at least fifteen segments were set during World War II or its immediate aftermath. Even “The Comedian” (one of many episodes about Playhouse 90’s second favorite subject, television itself) has the war buried deep inside: its protagonist, a surrogate for Serling, is an insecure comedy writer who plagiarizes a script left behind by a buddy killed in combat.

Act Four: Target For Three

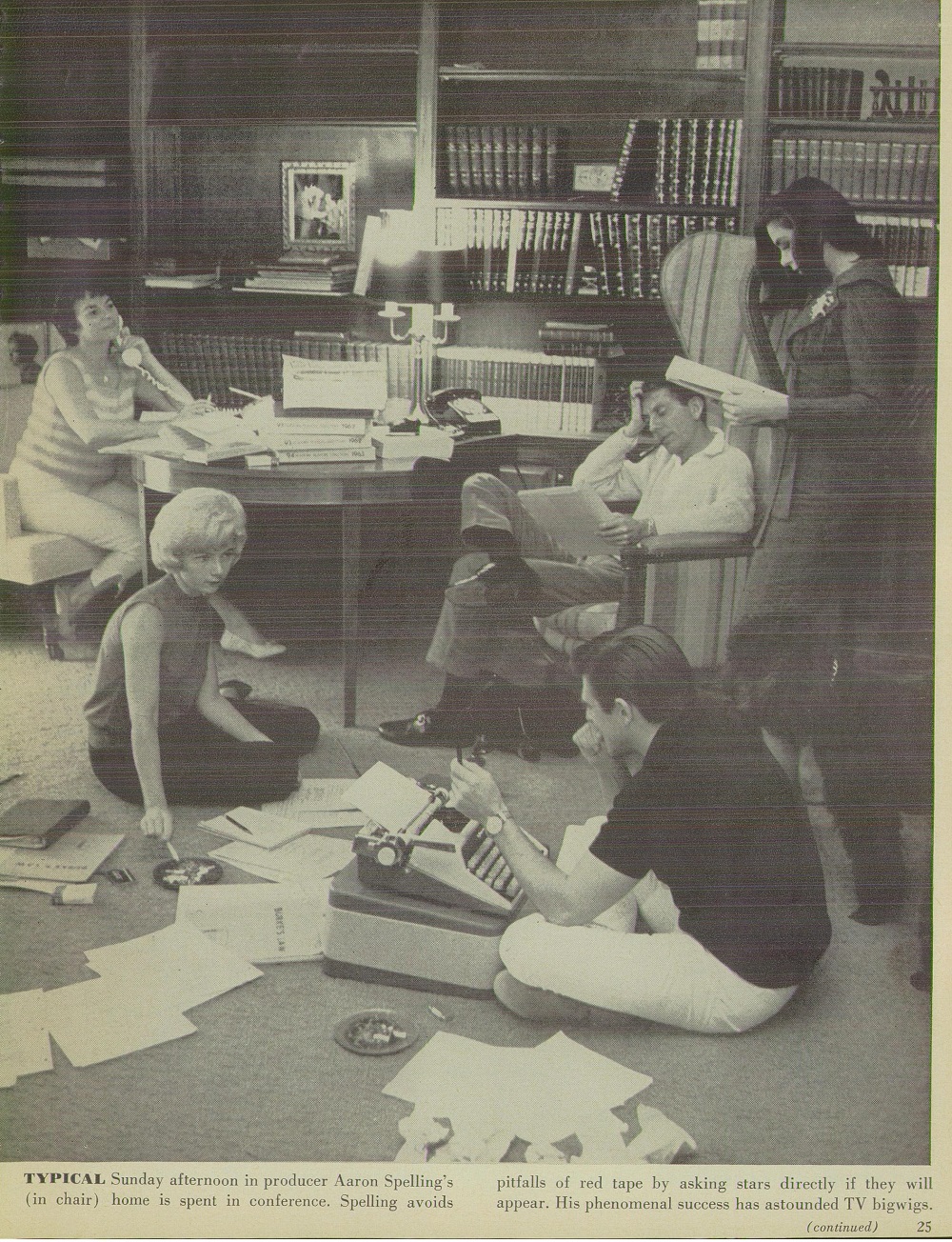

Martin Manulis burned out after two years. Playhouse 90 was a seven-day-a-week job, in which Sunday afternoon story conferences around Manulis’s pool were the closest thing to a respite. After Manulis quit in 1958, he would always brag that it took three men to replace him.

Those three men were superstars of live television: Fred Coe, who had pioneered the idea of commissioning original dramas for television on The Philco Television Playhouse; John Houseman, a founder of the Mercury Theatre, later famous in his acting role as The Paper Chase’s Professor Kingsfield; and Herbert Brodkin, an iron-willed up-and-comer who would go on to produce Emmy winners like The Defenders and Holocaust. Coe and Houseman were contracted to handle half a dozen segments each of Playhouse 90’s third season. The bulk fell to Brodkin, augmented with contributions by a handful of one-shot guest producers.

Manulis predicted that, under split authority, Playhouse 90 would lose some of its variety, as the three producers competed to produce the most significant, serious episodes. That’s precisely what happened – and, if anything, it made the series even better. All three of the new producers were New Yorkers who had produced “kitchen drama” anthologies as well as spectaculars, and to a certain extent they shifted the series back toward a model of small-scaled, character-driven works. Reginald Rose contributed “A Marriage of Strangers,” his answer to “Marty,” in which a fortyish man and woman (Red Buttons and Diana Lynn) marry just because they’re afraid of growing old alone. Steven Gethers’s keenly observed “Free Weekend” found a cross-section of middle-aged regret in the unlikely occasion of a summer camp parents’ visit. Some of Brodkin’s segments were so intimate that they were dwarfed by the size of the Playhouse 90 format – but even that, in a perverse way, served as a defiant tribute to a fading mode of television drama.

Brodkin’s preoccupation with the holocaust led to two bold, sprawling anti-fascist dramas, both starring Maximilian Schell and directed unsparingly by George Roy Hill: “Judgment at Nuremberg” and the lesser-known, but superior, “Child of Our Time,” a parable about a boy who wanders Europe during the war, neglected or abused by institutions of authority (the nazis, the communists, the church) as they occupy themselves with the “adult” business of genocide. Houseman produced the similarly allegorical “Target For Three,” a suspenseful assassination story notable for presenting Latin American revolutionaries in a heroic light during the same year that Castro seized Cuba, and the amazing “Seven Against the Wall,” a docudrama about the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre. Boasting a cast of fifty speaking parts (last-billed, as “Pete’s girl”: Louise Fletcher) and spilling over into a second studio, it was the ideal project for Franklin Schaffner, an uneven director whose skill for taming massively-scaled shows anticipated the best films he would go on to direct, Planet of the Apes and Patton.

Act Five: Gas

The network interference began in the first episode, “Forbidden Area,” a pulpy Cold War story adapted by Serling from a Pat Frank novel. CBS compelled Manulis to recast the voice of the U.S. president, because the original actor sounded too much like Adlai Stevenson, then a candidate for the office. Actually, it started even before that: “Requiem For a Heavyweight,” unmistakably a better script than “Forbidden Area,” was slotted as the series’ opener until a CBS executive decided it was too depressing. Censorship had always dogged the live dramatists who pushed the envelope, but Playhouse 90 was a bigger target than ever before. The executives watched rehearsals on video monitors in their offices. “It was a very Big Brother kind of thing,” said Frankenheimer. “A network executive’d come down with notes, and you did what they said. You fought up to a degree, but when you lost, you lost.”

Manulis had hoped to play the multiple sponsors against each other and keep any one of them from exercising too much control over the show, but the opposite happened. “They ganged up on us,” he said. “They chopped it up like a roomful of butchers at work on a steer.” “It” in that instance was Serling’s “A Town Has Turned to Dust,” a confrontational fictionalization of the death of Emmett Till, the black Mississippi teen who was murdered after he (allegedly) whistled at a white woman. The sponsors’ objections forced Serling to change an interracial romance to a flirtation, the lynching victim to a Latino, and the setting of the story to the Old West. Only four days before airtime, one sponsor, Allstate, delivered another blow: as insurance companies were unenthusiastic about people, even bad ones, offing themselves, the climactic suicide of the killer (Rod Steiger) had to be eliminated. “A script has turned to dust,” Serling punned.

The most troublesome sponsor was the American Gas Association (a trade organization for regional household natural gas suppliers, which in the ad segments billed itself not by name but, presumptuously, as “Your Gas Company”). During the second season the AGA had wanted Donald Bashor’s climactic trip to the gas chamber excised from “Portrait of a Murderer.” In that confrontation, Manulis prevailed. But “Judgment at Nuremberg” contained multiple references to the gas chambers used to murder Jews in the concentration camps, and the utility balked. Perhaps the phrase “death chamber” could be used instead? Brodkin and Hill refused to make the change, and the network countered by threatening to mute the word “gas” every time it was spoken on the air. Anyone else would have compromised at that point, but Brodkin – whose stubbornness and contempt for authority were legendary – let them do it. Although Hill was scapegoated and never directed Playhouse 90 again, Brodkin won a Pyrrhic victory. The deletion of the word was so obvious that the press took note, and raked CBS over the coals for what stands as perhaps the most craven and notorious incident of fifties television censorship.

Act Six: Old Man

In the fall of 1958, Frankenheimer began rehearsing Horton Foote’s adaptation of the William Faulkner story “Old Man.” The old man of the title was the Mississippi River, which Frankenheimer set out to recreate indoors. A gigantic water tank was constructed on Stage 43 for the scenes in which the river overflowed its banks and sent the main characters, a chain gang laborer (Sterling Hayden) and a pregnant woman (Geraldine Page), on a waterlogged odyssey. The tank was so heavy it cracked the foundation of the studio. “We’ll drown the actors,” worried Frankenheimer. The solution: cancel the live broadcast and shoot it all on videotape.

Although tape had already supplanted kinescopes as the method for recording the show’s live episodes for posterity, the difficulty of editing videotape had prevented it from being used to pre-record episodes. “Old Man” broke that barrier. “I made the first splice ever done on tape,” Frankenheimer recalled. “We had no instruments to cut it; we cut the master with a single-edged razor blade.” Instantly, everything changed. It helped that “Old Man” was triumphant, the quintessential Frankenheimer show. The director’s bold compositions concealed the artifice of the studio-bound tempest and zeroed in on the vulnerable performances at the center of the chaos. Most of Frankenheimer’s remaining episodes, as well as others from the third season and nearly all of the fourth, were pre-taped.

The “liveness” of Playhouse 90 had always been fungible; most episodes made use of filmed or taped inserts of scenes that couldn’t be staged live. The first season’s “The Comedian” contained forty such cues. But the directors quickly realized that shooting entirely on tape, although superficially similar to a live staging, removed all the urgency. Composer Jerry Goldsmith, who scored the many of the live episodes by conducting an eighteen-piece orchestra on an adjacent soundstage, said, “I felt the energy drop out of the performances, and it’s never been back.” Videotape was like the atom bomb – someone would have made it eventually – and during the sixties and seventies it would provide a lifeline for Playhouse 90’s few close successors, dramatic showcases like CBS Playhouse and PBS’s Visions, niche projects that would’ve been too expensive to do on film. But, just as J. Robert Oppenheimer had some second thoughts about his contributions to that other endeavor, Frankenheimer and Foote often lamented, in interviews over the years, their role in killing the medium they loved.

Playhouse 90, in any case, was after three years dying an actual death as well as an aesthetic one. The ratings had declined over time and, with $4 million of ad time left unsold, cancellation after the third season seemed certain. Hubbell Robinson engineered a fourth-season reprieve, but that was truncated at the end of 1959, after James Aubrey assumed the presidency of CBS and forced Robinson out. Aubrey, an especially rapacious and cutthroat executive, programmed shows like The Beverly Hillbillies and openly scorned anything highbrow. Immediately, Playhouse 90 was deprived of its regular timeslot, the episode order was cut, and the taped shows already in the can were rescheduled as occasional “specials.”

“Networks destroy things, you know,” said Herbert Brodkin. “It couldn’t be allowed to go unscathed. Too good for television. It had to be destroyed.”

A handful of hour-long anthologies – The U.S. Steel Hour; Armstrong Circle Theatre – limped into the early sixties, but when Playhouse 90 ended everyone knew the party was over. Critics rightly celebrate the series as a pinnacle; they less often notice that it was also an elegy. As it assembled the best and brightest of live drama, Playhouse 90 gradually undercut – or outgrew – what made their work unique. In its lavish budgets, its emphasis on celebrity, its cinematic aspirations, its shift away from liveness, the show sowed the seeds of its own obsolescence. After Playhouse 90, live television had nowhere left to go.

2023 Reading Roundup

January 30, 2024

The best new teevee-related book that I read last year was Patrick Stewart’s Making It So: A Memoir. Wince-inducing title notwithstanding, it’s about as far from the anecdote-after-anecdote, ghost-written-plot-summary-padded celebrity victory lap that I expect by default whenever I pick up a big star’s autobiography. Stewart writes about his real-life adversities, from his abusive, alcoholic father to the affair with a Star Trek guest star (Jennifer Hetrick, who recurred as a love interest for Captain Picard) that broke up his family, with a thoughtfulness that makes those stories as compelling as good fiction. Writing about yourself with candor and insight isn’t that hard – any glib egomaniac can entertain a reader that way for a few hours – but what Stewart pulls off here, a rich, literary evocation of the time and place that produced him, is much rarer. The actor was an avid, if not always humble, learner, genuinely curious about art and other people, and his prose exudes that quality in an infectious way.

Out of the hundreds of television professionals I’ve interviewed, maybe only three (Norman Lloyd, Del Reisman, and Ralph Senensky, for the record) have had what seemed like total recall, and Stewart might belong in that company. His evocation of the nondescript Yorkshire town where he grew up in poverty – he devoured the classics in an outhouse, the only place he could find any peace and quiet – was so vivid and flavorful that I plugged the address of the Stewart family’s modest row house, 17 Camm Lane (still there), into Google Maps and spent a bit of time wandering virtually through the streets of Mirfield, which appear almost unchanged since the teenaged Patrick roamed them. Reading Making It So is like walking around in a vintage Ealing or Rank movie, or maybe even one of Terence Davies’s trapped-in-amber recreations of the past. The poetry of Davies may not be on these pages, but the descriptive clarity certainly is. I was sad to see Mirfield recede into the past as Stewart launched upon his career, thinking we’d inevitably end up in more familiar territory, but no: his journey through regional, touring, and finally the most prestigious of Shakespeare companies supplies an equally fascinating glimpse inside an unfamiliar world. Even if this account were written by someone you’d never heard of before, you’d want to read it.

A minor detail that stayed with me is that Stewart is a car buff – an amateur racer who was more impressed with Paul McCartney’s MG than with Paul himself when he met the Beatle in 1964, and who decades later tooled around L.A. in a vintage Jag, shaking his fist at the traffic, at a point when he’d had enough success to hire a driver if he wanted to. Gene Roddenberry and Paramount’s colossal misread of Stewart wasn’t just cultural – the shiny pate as a signifier of middle age (I’m older, incidentally, than Stewart was during the first few months in which he played Picard); the intimidating RSC pedigree and the English accent, the populist aspects of the former and the Northern undertones of the latter both lost on your average American – it was a fundamental misunderstanding of his personality. This was not a captain who was going to sit behind a desk, and if the producers hadn’t yielded and let the star’s alpha energy shape the character, I’ll bet Jean-Luc Picard wouldn’t have lasted much longer than Tasha Yar.

Stewart’s oft-repeated Star Trek: The Next Generation origin story of arrogant priggishness loosened up by his fun-loving castmates is front and center here and, as usual, it scans more as a subtle reassertion of who’s boss – leadership through grace rather than force – than the exercise in self-deprecation it pretends to be. Also repeated from many an interview, and couched within a superficially respectful portrait, are the subtle digs at Roddenberry, more interested in talking about golf than Stewart’s problem of bringing his character to life; Sir Pat was a good fencer in Shakespeare school, and he’s still deft with the blade. (And he validates my pet theory that golf is a great tell for exposing presumably interesting people – Sean Connery, Bill Murray, Barack Obama – as bores.) Like most of us, Stewart is the hero of his own stories; he clearly enjoys stardom, and I suspect he craved fame, and sought the center of attention even before he had achieved it. Yet somehow the modesty that is his default stance in Making It So doesn’t feel feigned. I’d surmise this is because Stewart is the atypical actor who has his shit together, who figured out who he was as a person before he had success in his profession. But then maybe that’s my fundamental misread; if I ever hang out with him (and frankly, I’d like to), I reserve the right to decide that he’s insufferable, and just cannier than most at playing a down-to-earth bloke.

As for the topics the fanboys will make a beeline for – Dune, Star Trek, the X-Men franchise – Making It So is candid but undeniably perfunctory. At times, Stewart’s efforts to engage with his most famous credits are hilariously perfunctory, as when he settles in for a full ST:TNG marathon, inviting the reader to re-watch along with him, then gets bored after covering three or four episodes (including such milestones as “11001001”) and meanders, without ever getting back on track, into several affectionate pages on guest star David Warner, whose mid-sixties stage Hamlet had a huge influence on the future Sir Pat. If your only reaction to this endearing book is to get mad about Stewart’s comparative disinterest in the projects that made him famous, well – look, when I watched William Shatner’s “Get a life” sketch on Saturday Night Live, I didn’t see the humor in it at all. How dare Captain Kirk dismiss his legacy and his fans (meaning me) with such a thoughtless, self-indulgent gesture? I was furious! The thing is, though, I was ten years old.

At the other end of the celebrity memoir spectrum, and somehow bearing an even worse title, sits To the Temple of Tranquility … And Step on It!, by character actor Ed Begley, Jr., whose nearly sixty years in television stretch from My Three Sons to Better Call Saul. First of all, I’m still processing the revelation that Ed Begley pere could, as they say, get it: that the growly character actor who looked 68 when he was 48 (his age when Ed, Jr. was born) was a serial philanderer who enjoyed longterm relationships with several much younger women. One of them, an NBC page, was Ed’s mother, although nobody bothered to tell Junior this until he was a teenager and the woman was dead. Juicy as that is, it’s all downhill from there, as Ed loses the thread of his perhaps-parental-trauma-triggered slide into addiction and undistinguished acting, both of which he overcame in the early eighties (via AA and some good teachers, respectively), for a series of self-indulgent forays into name-dropping and star-fucking. Jack Nicholson and Marlon Brando and Eve Babitz and Ed Ruscha and many more are in here, but Begley finds little of substance to say about them. Begley’s laudable social and environmental activism presents itself mainly in the form of rueful “yeah, I’m THAT guy” quips; when Cesar Chavez turns up, all we learn about him is that Chavez somehow managed to tolerate the presence of Ed Begley, Jr. The one insight I’ll retain from this book is that Victor Ehrlich – the talented but preening, glib, and unbearably obnoxious doctor Begley played with great verve on St. Elsewhere, his breakout success – barely existed on the page when Begley was cast; the writers assured him that they would build up the character in response to his performance. Talk about telling on yourself.

Speaking of St. Elsewhere: Because it’s slim, badly copy-edited, and from a tiny publisher, I assumed Bonnie Bartlett Daniels’s Middle of the Rainbow would be just a footnote to her somewhat better-known husband William Daniels’s thorough and very entertaining 2017 autobiography, There I Go Again. Call me sexist, then, because Bonnie’s account is just as vital as Bill’s. It is legitimate, I think, to look at them as complementary, perhaps best read in tandem, and not just because Bartlett (unlike in her acting work) adds her married name to her byline. I remember There I Go Again as a terrific read, honest and mature, but Bartlett is so unsparing in her depiction of her spouse – his emotional repression and unthinking sexism, his phony New England-ish accent (an affectation adopted off- as well as on-screen), the infidelity and alcoholism that led to their move to Los Angeles and the revival of her dormant screen career – that I felt the urge to go back and see how much of all that Daniels had fessed up to. (I did check to see if Daniels mentioned the affair, with an unnamed Broadway producer, that almost split the couple up in the late sixties or early seventies. It’s not in there, and in that and other instances, it’s hard to intuit whether Daniels was being discreet about details that might have embarrassed Bartlett, or if Bartlett is punishing Daniels for soft-pedaling his bad behavior in a way that cast her own choices in an unflattering light.)

Like Daniels, and pretty much every other performing artist active in the immediate post-war era, Bartlett spent a lot of time in analysis, and that experience informs her perspective on her personal life as well as, I suspect, her approach to her craft. If Daniels’s domineering stage mother provided his foundational trauma, then Bartlett’s seems to have been a father who was inappropriately sexual around his kids. In the family tradition, Bartlett herself teeters on the verge of oversharing on matters of intimacy, but her still-seething contempt for the various industry men who harassed her (and worse) feels earned and timely – even though, maddeningly, she opts in most cases not to divulge their identities, even of the Edge of Night co-star who raped her at the peak of her early stardom in television. A shame that this fellow will go to his grave, or already has, with his legacy untarnished.

Julia Bricklin’s concise and very useful biography of Hannah Weinstein is the first new book in a while that belongs on your blacklist shelf – wait, you do have one, right? My fellow blacklist nerds will recognize Weinstein as the impresario behind Sapphire Films, which kept many of the best blacklisted writers gainfully employed, amid a tangled thicket of noms-de-plume, on several action series made on the cheap in England between 1955 and 1960. Those shows, especially the first one, The Adventures of Robin Hood, were configured on purpose to incorporate some basic leftist tropes (steal from the rich, etc.) while remaining ideologically po-faced enough to sell to American networks. I can’t attest to how much lefty propaganda Waldo Salt, Ian McLellan Hunter, Ring Lardner, Jr., and others may have smuggled into Weinstein’s quintet of derring-do half-hours; I hope it was a lot, but I confess I’ve been defeated by the talky, formulaic storytelling any time I’ve taken a whack at them. Most recently it was the swashbuckler The Buccaneers, and I lasted exactly three episodes, even with pirate captain Robert Shaw on board. (Get it? “On board”? Because boats.) Four Just Men, the last Weinstein series to launch and the only one with a contemporary setting, remains untouched but close to hand, thanks to the DVD set from Network Distributing, the abrupt collapse of which – sorry for the digression, Hannah – was a major blow to anyone interested in British television history, and certainly the biggest bummer (even more than the end, apart from streaming, of Netflix) in a year of depressing milestones in the home video landscape.

Anyway: The handful of producers who stuck their necks out and succeeded in throwing work to starving leftist writers in the fifties and early sixties are a fascinating lot. They’re often mentioned in the artists’ accounts of the era but none of them has been at the center of one until now. Charles Russell, the failed Hollywood actor turned New York CBS staffer who kept a different constellation of writers (including Walter Bernstein and Abraham Polonsky) working in secret on live shows like Danger and You Are There, is probably more asterisk-famous than Weinstein, just because that tale was turned into a popular movie, Martin Ritt’s The Front. I’d love to know more about the unlikely profile in courage that was Russell, who after his one great moral triumph slid into an epic personal and professional decline. Yet Weinstein’s story may be even more compelling, if only because she did it backwards and in high heels.

If Weinstein has been unjustly neglected by blacklist historians, it’s probably less because of her sex than because she seemed to come out of nowhere. Neither a Hollywood or a Broadway figure but a labor organizer and political operative, Weinstein fled the US with her three daughters (but not her husband, who bailed as soon as HUAC circled) and learned everything she needed to know about production by hanging around a few French film sets. It wasn’t, but she certainly made her entry into television producton look easier than anyone else ever did.

At first Bricklin’s book is a little dry, at least relative to its hot-stuff title – Red Sapphire! – and part of that may be because she had no access to relatives or family accounts and thus confines herself to a uniformly external perspective on Weinstein and her work. (Indeed, if I’m interpreting a few cryptic asides correctly, Bricklin may have faced active opposition to a more authorized biography. She even seems, and perhaps I’ve simply been infected the paranoia of the McCarthy era here, to have avoided mentioning Weinstein’s daughters by name as much as possible; one of them, Paula, whose fame as a movie producer has far eclipsed that of her mother’s, is listed in the index exactly once.) This proves less of a handicap than you’d expect, although I think it’s at the root of my only major qualm about Red Sapphire, which is an inclination (signaled in the introduction by some wide-eyed and already dated asides on Trump and 1/6) to smooth over distinctions between Weinstein’s radical activism and the liberal mainstream. In the maddening absence of sources charting Weinstein’s own intellectual evolution, Bricklin’s evident disapproval of Soviet communism (a position ultimately adopted by a majority of blacklistees, but by no means all of them) risks standing in for her subject’s point of view. Who knows; Weinstein was a pragmatist, and she may well have joined the Vote Blue No Matter Who crowd had she been unfortunate enough to live into the current century. But would she really have seconded Bricklin’s brief, dismissive assessment of Henry Wallace’s 1948 third-party presidential run – which, in her most high-profile pre-television job, Weinstein managed and may have been the real power behind – as having “suffered from ill-defined, or mixed, or even absent messaging”? To my mind, the Wallace campaign is one of the most optimistic moments in American electoral politics. But we simply don’t know what conclusions Weinstein chose to draw from its defeat.

Overall, Bricklin’s research is impressively thorough, and her assessments of her subject are cogent and even-handed (especially with regard to the perennial conundrum of the blacklist-breakers, that is, whether they were acting on principle or exploiting top talent at bargain rates). The course she charts through the convoluted backstory of Weinstein’s unique operation clarified my previously vague understanding of how it came into being and worked in practice. This was, after all, a British company making television for the American market, with British actors and crew, financed by British entrepreneurs and produced by an American, and written clandestinely by American writers. Those writers were, in one of the book’s most compelling strands, creatively frustrated by their remoteness from the set and susceptible to paranoia and irritation over the labyrinthine process devised to protect their anonymity (and Sapphire’s foreign sales): every story memo and paycheck had to pass through an absurd Rube Goldberg relay of multiple intermediaries. One source Bricklin and I shared, the writer Albert Ruben, who was a story editor at Sapphire early in his career, threw up his hands when I presented him with a list of Robin Hood’s pseudonymous credits and asked if he could decode them. Bricklin was more tenacious with Ruben, and resourceful in response to the problem that nearly all of Weinstein’s other collaborators died before she began work. Her solution was to track down the children of many of them and press them for second-hand memories, and she incorporates this material into her work more persuasively than I would have thought possible. (Bricklin also makes excellent use of Weinstein’s FBI file.) The story of Sapphire eventually turns into a colorful and dramatic one, worthy of screen treatment as a distaff The Front, in which our heroine finds an enchanted forest (actually a woodsy Surrey estate that Weinstein bought and turned into both a residence and a production center, so that she in fact lived among her rubber-armored knights and their flesh-and-blood horses for a time) and runs afoul of a most dastardly villain, who casts her out of it. (I’m not going to “spoil” that last part.)

Although the Robin Hood section is detailed (even to excess; a ten-page chapter describing a press junket to the real Sherwood Forest seems to exist more because Bricklin found a thorough account of it than because of the event’s significance), there’s a bit of just-get-it-done fatigue following the collapse of Sapphire. Weinstein’s portfolio as a film producer was modest but it includes a masterpiece, John Berry’s Claudine, and it’s a big disappointment to see that film summarized in a paragraph. The next ten years of Weinstein’s life – comprising her only other film credits, a pair of Richard Pryor vehicles, and then her death in 1984 – receive only two paragraphs. If a mother lode of the Weinstein family’s archives ever opens, I hope Bricklin will get the chance to revise and expand her chronicle.

And, some quick takes ….